Savage Arms: Long-Range Shooting Specialists

News Events

Create a FREE business profile and join our directory to showcase your services to thousands.

Create my profile now!

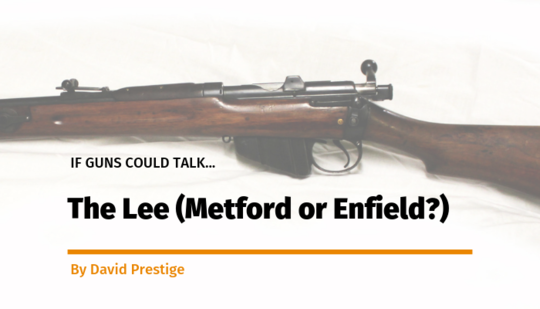

...They would have a tale to tell. At least, that’s the theory. My latest acquisition is, however, sticking firmly to the “no comment” routine. I know that its first name is Lee, but is its surname Metford or Enfield? Body-wise, it’s mostly Metford, with the signature grooves and recess in the woodwork, and it shares the Metford characteristic of having no safety catch. It has the groove underneath the stock to accept a clearing rod, but the metalwork around the muzzle doesn’t allow for one to be inserted. Experts tell me that the rifling is definitely Enfield and there is a stern warning stamped in the steel which says “cordite only”. Born in Birmingham? Well, according to the BSA markings, it’s definitely a Brummie.

A bit like Paddington Bear the rifle came with a note pinned to it, but what it says confuses things even further.

For starters, leaving aside anything technical, it looks in much too good a condition to have been hauled around the veldt and kopjes in turn-of-the century South Africa. One online expert on a forum I consulted wondered if it had been refitted as a civilian target rifle. Certainly, there are no obvious military markings anywhere, so perhaps that might be part of the story? It does, however, have the distinctive volley sights – a range disc nearest to the muzzle, and an aperture sight at the bolt end. In theory, this enabled a rifleman to use the gun rather like a miniature howitzer, and rain bullets on the enemy a thousand yards or more away.

With the rifle remaining resolutely tight lipped about its life story, I started to look into the story of the City of London Imperial Volunteers mentioned in the provenance, and discovered a fascinating but ultimately tragic story. I had an evening engagement in London, and so I spent the afternoon in The British Library intending to read all there was to know about Lees, both Metford and Enfield, but my curiosity about the CIV was about to take me off in a different direction.

The City Imperial Volunteers were pretty much what the name suggests, and they certainly did go off to fight the Boers and were involved, among other things, in the action whose name gave rise to many a music hall jest in the subsequent years – The Relief of Ladysmith. The CIV was something of a gentlemen’s club, and as I scanned through the list of the great and the good who had sailed off to Africa, one name grabbed my attention straight away, as he was the author of an adventure story that had I had enjoyed in younger days.

Robert Erskine Childers was born in London on 25th June 1870, and his mother was from a distinguished Anglo-Irish family. After studying classics and law at Cambridge, he worked in the House of Commons, but developed a passion for sailing. This was to have profound consequences. His Boer War service was something of a disappointment to him as, after seeing some action as an artillery driver, he was invalided out with trench foot.

His political views were focused on two issues: firstly, he was convinced that German expansionism was a huge threat to Britain, but he imagined that the main thrust of any action would be by sea, and that it would come across the North Sea in the direction of Britain’s lightly defended east coast. Using his fascination with sailing and his knowledge of the Baltic and the waters around the Friesian Islands, he wrote The Riddle Of The Sands in which British secret agents uncover a plot where a German army would be spirited across the waters to invade Britain. Published in 1903, it has never been out of print and has been filmed numerous times. Childers had one other preoccupation, and that was the cause of Irish nationalism. Part two of this feature will look at how Childers, after distinguished service in The Great War, turned his attention to the Irish Problem, with fatal consequences.

Having written a bestseller with The Riddle Of The Sands, Childers became obsessed with the cause of Irish nationalism. On the eve of WWI, he put his skills as a sailor to what he thought was good effect, and in his boat Asgard he smuggled 900 Mauser Gewehr 71 rifles into Ireland for use by the Irish Volunteer Force.

Despite his growing dissatisfaction with what he saw as British imperialism, Childers volunteered for service again in 1914, and was commissioned as Lieutenant in the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve. He eagerly embraced the new challenges posed by the war in the air and, although never training as a pilot, did vital work as a navigator, observer and intelligence officer. He was awarded the DSC in 1916.

He saw the defeat of the Easter Rising in 1916 as a tragedy, but Childers remained loyal to Britain. When the war ended, however, he threw himself wholeheartedly into the struggle for Irish independence and moved to Dublin, where he was frequently consulted by leaders such as Eamon DeValera and Michael Collins. The biggest divide in Irish politics at the time was not between Britain and Ireland, but between the factions within the Irish nationalist movement. Michael Collins was assassinated in 1922 and that same year, Childers himself fell foul of the internal enmity, and was arrested on a firearms charge. He was sentenced to death, and executed by firing squad on 22nd November 1922, at Beggars Bush Barracks, Dublin.

One of the many ironies of this story concerns Childers’ son. Erskine Hamilton Childers was aged 16 at the time of his father’s execution. He became a prominent Fianna Fáil politician, and in 1973 served a term as President of the Irish Republic. Father and son are pictured below.

To go back to where we started, I’ll finish with a description of the gun itself. It may be odd to describe an instrument of death as ‘elegant’, but there is no other word for it. It is long, slim and beautifully balanced, and although I am a lifelong admirer of the SMLE and its many variants, this gun looks as though it was designed by an artist rather than a tradesman. Best of all, though, is that it shoots like a dream. From 25 metres to 600 metres, point it, squeeze the trigger, and it serves up impressive groups. I might try a longer range at Bisley next year, but I suspect my ageing eyes will let this beauty down.